A series profiling American Jewish service in the First World War

A series profiling American Jewish service in the First World War

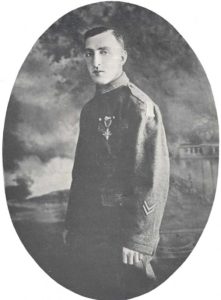

Abraham Krotoshinsky

Savior of the Lost Battalion

Before the war, the “Savior of the Lost Battalion” was still an immigrant barber in the Bronx. Krotoshinsky came to New York from Płock, part of the Russian Empire in Poland. He’d left there specifically to escape military service. Years later, he would write “As I look back at it now, it all seems strange. I ran away from Russia and came to America to escape military service. I hated Russia, its people, its government, in particular its cruel and inhuman treatment of Jews. Such a Government I refused to serve.”

His attitude toward military service changed drastically in his adopted country. Krotoshinsky described himself as an ardent patriot. When the opportunity came to join the Army and serve in the war, he embraced it. He trained at Camp Upton. The 77th Division drilling at Upton was known as the “Melting Pot” division. It was filled with immigrants and the children of immigrants living in New York. An estimated 25% of the 77th was Jewish. Most were drafted and had no military experience. They had to overcome language barriers and cultural differences. This didn’t keep them from becoming one of the most celebrated American divisions during the war.

Krotoshinsky was assigned to the 307th Infantry and shipped to Europe. Before long, they were in the midst of the fighting as a replacement for the 42nd Division. Krotoshinsky recalled being welcomed by the Germans, who sent up a balloon with the message “Goodbye, 42nd — Hello, 77th.” Not long after the welcome, the 77th was hit with a barrage of German shells and gas attacks.

The Lost Battalion earned its name in the Argonne Forest in October of 1918. Nine companies from the 307th, 308th and 309th regiments that made up the “battalion” had advanced too far. They were separated from the rest of the Allied lines and surrounded by German forces. Conditions were horrible. Food and water were in short supply. The Germans were still attacking. Perhaps worst of all was the friendly fire from American forces that continued to fall on the lost men. Messengers had been unable to break through the German lines to report to headquarters and get the American shelling to stop.

When a request was made for another round of volunteers to try and reach headquarters, it was Krotoshinsky who answered the call. He described it:

I started out at daybreak, but it did not take me long to be aware I was a target for the Germans. I ran across an open space, down a valley and up a valley into some bushes. I remember crawling, lying under bushes, digging myself into holes. Somehow or other—I don’t know how to this day—I found myself at nightfall in German trenches. I saw several of them smoking cigarettes. I knew that if they knew of my visit the greetings they would have extended to me would not be any too friendly. I hid under some bushes, lying prone and acting dead. A German, who, judging from the pressure, never knew anything about a reducing diet, stepped on one of my fingers, but I kept myself from making any outcry. Later I crawled into another deserted Geman trench. You can imagine the thrill I got when I heard good English words spoken. No music ever sounded better. But even now I had to face the problem of first convincing them I was a friend and second, of entering the lines as I did not know the password. I began shouting, “Hello! Hello!” After several minutes of yelling, a scouting group of American soldiers found me and took me to headquarters, where I delivered my message, giving them the position and condition of our battalion.

“We need medical assistance and food,” I told them.

In the process of reaching headquarters, Krotoshinsky was gassed and wounded. He became celebrated as one of the heroes of the Lost Battalion (though perhaps overshadowed by a heroic pigeon with the same assignment). AEF Commander General Pershing personally presented Krotoshinsky the Distinguished Service Cross with the following citation:

He was on liaison duty with a battalion of the 308th Infantry which was surrounded by the enemy north of the Forest De la Buinonne in the Argonne Forest. After patrols and runners had been repeatedly shot down while attempting to carry back word of the battalion’s position and condition, Private Krotoshinsky volunteered for the mission and successfully accomplished it.

After the war, Krotoshinsky was hailed as the “bravest of the brave” in the New York Times and elsewhere. He chose to study agriculture at the National Farm School at Doylestown, Pennsylvania. In 1921, his Zionist ideals inspired him move to Palestine. He worked there on a farm, married and had children. In 1926, he and his family returned to the U.S. He worked for the U.S. Postal Service the remainder of his life. Krotoshinsky died in the Bronx in 1953.