A body of an American solider lying peacefully in the snow in a battlefield in Belgium. A Jewish boy in Brooklyn orphaned twice by World War II. And the world-renowned photographer who connected the two. This is their story.

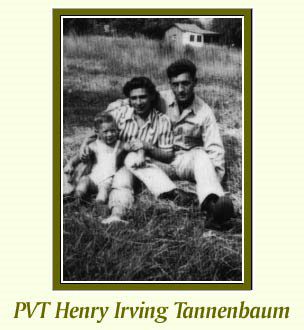

Samuel Tannenbaum was born on July 10, 1942, in Washington DC to Henry and Bertha Fiedel Tannenbaum. Less than two years later, Henry was drafted into the United States Army. Bertha and Sam moved to Williamsburg section of Brooklyn to be closer to their families. After training at Fort Meade, Maryland, Henry was assigned to the 331st Infantry regiment, 883rd division, and was shipped to England. His rifle platoon subsequently fought in battles in France and Luxembourg, which garnered Henry several medals.

Between December 16, 1944, and January 25, 1945, on the border of Belgium and Luxembourg, Allied and German troops were engaged in what would later be known as The Battle of the Bulge, one of World War II’s deadliest fights. On January 11, Tannenbaum and his division were ambushed by German soldiers. Only one person—Platoon Sergeant Harry Shoemaker—survived.

When Shoemaker escaped and returned to regimental headquarters, he told the sentry, Corporal Tony Vaccaro, the details of the massacre. Vacarro and Shoemaker returned to the site the next morning. The two stared at the horrible carnage. If the soldiers had survived, the Germans murdered the wounded and stripped the corpses of their watches and other valuables. Then the Germans rolled their tanks over the dead and dying, crushing them into grotesque, mangled shapes.

Only one figure looked peaceful and untouched by death. The prone body of a lone soldier lay face down, his boots, backpack, helmet and rifle showing through the white snow that blanketed him. Vacarro pulled out his Argus C vintage camera and captured the scene. Afterward, Vaccaro and Shoemaker cleared away the snow to discover the dead soldier was their army friend, Private Henry Tannenbaum.

Henry Tannenbaum was buried in Henri-Chapelle Cemetery in Belgium with plans to bring his body home. Bertha Tannenbaum, his widow, falsely believed that the transfer would adversely affect her four-year old-son Sam’s war orphan benefits. She was against reinterment. Henry’s family fought Bertha’s decision and won, and Henry’s remains were returned to New York in 1946. The disagreement caused the widow’s estrangement from the Tannenbaums, isolation from her own family, and her growing mental deterioration. In her mind, Bertha believed that Henry was still alive and working secretly for the FBI. Sam’s childhood was filled with his mother’s shouting at the ghost of her husband, several psychotic episodes, and even an attempt to kill her son and then commit suicide. “The bullet that killed my father also destroyed my mother’s mind and ended my childhood,” said Sam.

With “my father dead and my mother crazy,” Samuel was forced at a young age to raise himself. He took care of household chores, did the shopping, and, through conniving, even paid the bills. When he was thirteen, he arranged for his own bar mitzvah, fortuitously connecting with his father’s family through a Hebrew school classmate. Upon graduating high school, he moved into his own apartment and, supporting himself with a war orphan scholarship and odd jobs, graduated from Brooklyn College.

While Sam was in college, Bertha was evicted from her apartment and was committed to a state mental institution. The eviction resulted in the destruction of the family’s belongings, including all artifacts of Sam’s family’s history. Outside of his name and the date of his death, Sam knew nothing about his father. Sam married, (Bertha didn’t come to the wedding; she thought it was another FBI plot), had a daughter Lisa, and divorced. Bertha met and fell in love with Sam’s fiancée Rachel, promising her that Henry would return in time for the wedding.

Meanwhile, with the help of the extended family, Sam was putting together pieces of his father’s past. Henry was regarded as intelligent with a great sense of humor. He had graduated from the same grade school, high school, and college as his son. Henry worked for the Office of Price Administration and taught Sunday school at a local synagogue. Henry had an inherited bleeding disorder which probably caused the private’s quick and peaceful death in Belgium on that bitter cold January day, and that unfortunate disorder was passed on to his son.

In 1986, three years after his mother died, Sam invited his father’s family to his daughter Lisa’s bat mitzvah. His first cousin, Henry’s niece, gave Sam a Victory Mail correspondence that identified Private Henry Tannenbaum’s regiment. Sam now had the tool he needed to further research his father’s military history.

In 1995, he and his wife Rachel journeyed to Seattle to attend the premiere meeting of the American World War II Orphan Network (AWON). The national organization was composed of the Gold Star children and others classified by the Veterans Administration as war orphans.

At a second AWON meeting in Washington DC in 1996, Sam met several people from Luxembourg who came for the express purpose to meet and thank the children of their liberators. Sam invited several to his home. One of the guests, Renee Schloesser, a journalist, published the Tannenbaum story in a series of articles in a Luxembourg newspaper. Another attendee, Jim Schiltz, was also impressed with Sam’s search. When he returned to Luxembourg, Schiltz found a book of photographs of World War Two and specifically, of the 331 Regiment in Luxembourg taken by the sentry Tony Vacarro.

The picture taken on the battlefield in Ottre was not the only one Tony Vaccaro had captured. Michaelantonio Celestino Onofrio Vaccaro had carried his Argus C with him when he, along with thousands of fellow Allied soldiers, stormed the beaches at Normandy on D-Day. Tony—at first surreptitiously and then with his superiors’ approval—went on to take thousands of pictures of Allied campaigns in Normandy and Germany.

After the war, Tony stayed in Europe through 1949 to document post-war life in Europe. When he returned to the States, Tony became a photo journalist for Life and Look magazine, photographing famous figures including John F. Kennedy, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Sophia Loren. Throughout his career, “White Death: Photo Requiem for a Dead Soldier, Private Henry I. Tannenbaum” circled the world through multiple exhibits and books and had become the iconic image of the Battle of the Bulge.

Schiltz also found out that Tony was alive and living in New York City. In 1997, the orphan and the photographer met for the first time. Tony gave Sam a professional print of the photograph. Tony’s greatest joy besides meeting Sam and his family was taking a picture of Henry’s grave in Mount Hebron Cemetery, New York City. For Tony, that picture brought him closure after more than fifty years.

In 2002, Sam and Rachel Tannenbaum and Tony Vaccaro flew to Europe as guests of the grateful citizens of Luxembourg and Belgium. The Tannenbaums met with the countries’ war orphans. They visited the Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery where Henry was originally buried. In Ottre, Belgium, Sam and Tony placed a wreath at the AWON monument, dedicated to “PVT Henry Irving Tannenbaum and other members of the 83rd Infantry Division.” For Sam, it was a “trip of a lifetime.”

Fifty-seven years after the then-amateur photographer shot “White Death,” Sam Tannenbaum and Tony Vaccaro visited a beautiful tree-filled spot in Ottre, Belgium. The former battle field is now a Christmas tree farm called Salm Sapin in French. And in German? Thanks to the famous German folk song now identified with Christmas, it would be associated by many with “O Tannenbaum.”

Sam’s home in Kissimmee, Florida, is filled with artifacts from his family’s history—pictures, books, his father’s medals, and a replica of the bracelet Henry was wearing before it was stolen by the German soldiers. “I may not have had the opportunity to tell my parents that I love them,” said Sam. “Through telling their story, I believe I am honoring them. And that, is, after all, what the Fifth Commandment tells us to do.”