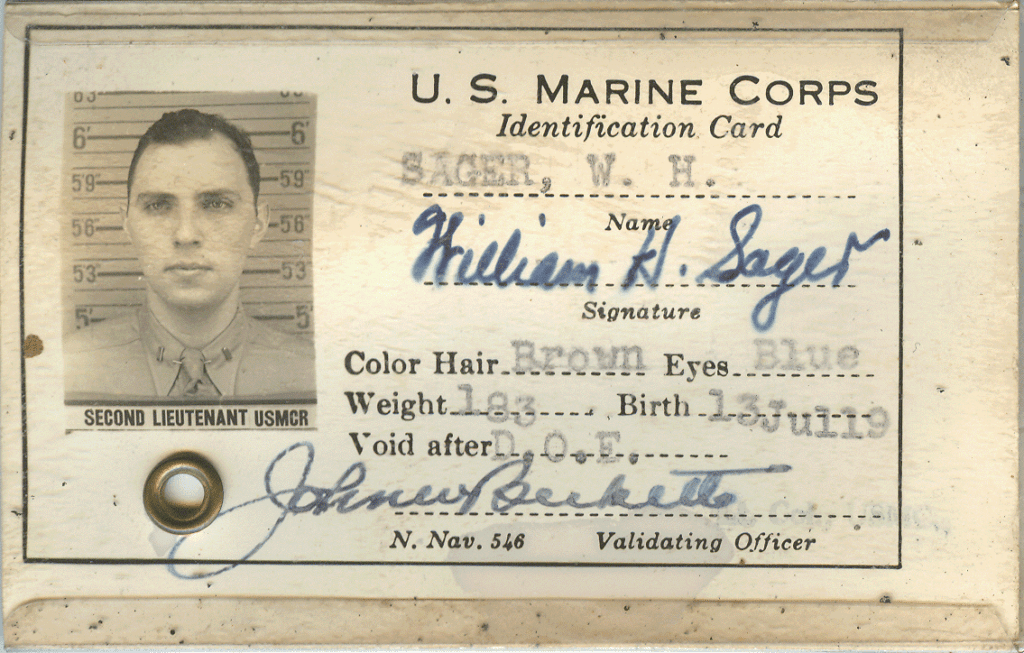

William Sager and Herman Abady were close friends at the University of Virginia (UVA) before Pearl Harbor was attacked and the U.S. went to war. Both Jewish, the two shared many experiences. In 1939 and 1940, both had completed the Marine Corps Platoon Leaders Course. Those who completed the course and passed a rigorous physical examination received a commission as a second lieutenant when they graduated from college. Sager graduated in June of 1941 and Abady continued in law school. Both were commissioned as officers in the Marine Corps. Sager took a job in Richmond where he lived in Abady’s home. Both were called to active duty in 1942 and sent to Marine Corps Basic Officers School in Philadelphia.

After finishing Basic Officer’s School, both Sager and Abady were assigned to K Company, 3rd Battalion, First Marine Regiment, First Marine Division. Sager commanded the First Platoon, Abady commanded the Third. They were sent to the Pacific. The UVA roommates would fight the Japanese side by side.

Before leaving, Sager married his girlfriend Elizabeth Mopsik in what she described in her memoir as the first Jewish wedding in Charlottesville in more than 50 years. It would only be a few weeks before he would ship out. Abady gave up his last chance for leave in the U.S. and volunteered to take Sager’s duty so his friend would have time with his new wife.

The regiment went overseas in early June of 1942, first to New Zealand and then to Guadalcanal. In August, the Marines captured the air field there. Initially, the Japanese provided little opposition. The Americans would promptly rename it Henderson Field. It provided an important strategic position in the region that would affect the course of the war in the Pacific.

More challenging combat came in August when the Japanese sent wave after wave of troops at the Marines’ heavily armed defensive positions during what’s known as the Battle of the Tenaru River. The Japanese suffered tremendous losses. This is considered the Americans first major victory over the Japanese in a land battle. It provided a turning point in the war.

After the defeat, the Japanese prioritized retaking Henderson Field. This began with daily bombings. In later interviews, Sager said you could set a watch by the daily arrival of the Japanese bombers launched from other islands in the area. The 3rd Battalion was positioned on the eastern end of the island to prevent Japanese access to the air field.

Rosh Hashanah

Though they’d only been on Guadalcanal a month, when Rosh Hashanah arrived on September 12th, the men of the battalion were already combat hardened. Sager described the 1942 high holiday services in an account written on Rosh Hashanah 40 years later. About a dozen or so of the battalion’s Marines and “a few Navy people” hiked back to Henderson Field and gathered on the airstrip to hold services. This was the same airstrip being consistently bombed by the Japanese.

The division chaplain was a Lutheran minister who met with the men briefly with “Gut Yontif” greetings before leaving the Jewish men to run services themselves. Services were led by “A young PFC from Washington, D.C.” who carried a tallit and a Jewish Welfare Board prayerbook in his pack. “When we came to the part in the service about who shall live and who shall perish by the sword, we made jokes about meeting the business end of a samurai sword in a bonzai charge, but a Navy doctor among us gave unequivocal assurance there was a ‘loop hole’ and the evil decree could be averted by giving generously to charity.” The humor was used to relieve the extreme tension of being under siege on an island that seemed impossibly distant from home.

Rosh Hashanah services were short that year and provided only the briefest respite from war. They came to an end when the Japanese bombers arrived on their usual schedule. At noon the bombs were falling on Henderson Field. “When the bombing was over, we shouldered our 1903 Springfields and hiked back to our positions on the Lunga River, which because of the inaccuracy of our maps, was called the Ilu River. For the Marines on Guadalcanal, Rosh Hashonah (sic) 1942 was over,” wrote Sager.

Battle at the Overland Trail

That same day marked the beginning of the Battle of the Bloody Ridge (or Battle of Edson’s Ridge), one of the major battles on Guadalcanal. Sager and Abady’s company were not at the ridge, but would play a key role on a different part of the island. Sager and Abady’s K Company fought in what is now know as the Battle at the Overland Trail. Both of them commanded rifle platoons. On September 13th, they engaged with the Japanese Kuma battalion in a furious battle to protect Henderson Field along the Overland Trail also known as the Amphibian Tractor Trail. The trail was behind the K Company line. While the Japanese sent the majority of their forces to the ridge, If they could take the trail, they would have easy access to Henderson Field and headquarters on that route.

The week prior to the battle, Sager’s platoon patrol had discovered some shoes and cigarette packages, evidence that Japanese troops were close to the battalion’s position. Sager had reported to Division HQ that the Japanese had begun working their way through what had been considered impenetrable jungle. There appeared to be large numbers of Japanese coming from the South in position to attack Henderson Field. This intelligence allowed the Marines to prepare the defense of Bloody Ridge in advance of the attack.

The night of September 13th at the Overland Trail, as the Japanese advanced, Sager’s 1st Platoon defended the right flank. To their left was a large gap. If the Japanese had discovered this opening, they could have walked up to Henderson Field with little resistance. Abady’s 3rd Platoon was split into two groups. One was on each side of the trail.

The Marines spotted the Japanese Kuma Battalion advancing and were able to engage them before the attack on the Overland Trail and K Company. This removed the element of surprise and enabled the Marines to prepare. When the Japanese reached the Marines lines, intense fighting began. The Japanese were desperately trying to reach the airfield. The Marines line was thin. There weren’t enough men to cover the area. Some Japanese broke through a barbed wire fence that had been erected and engaged in hand-to-hand combat.

It was Abady’s platoon that saw the heaviest fighting with the brunt of the attack coming at them. By early morning, the fighting had become hand-to-hand and bayonet combat. The Marines’ line held as Japanese forces broke apart. After the battle, over 100 Japanese bodies were found in front of K Company’s area, most of them in front of Abady’s position. The Japanese never identified the gap at Sager’s right that would have allowed them to easily reach the air field. The Americans held the Overland Trail and Henderson Field. The successful defense of Henderson Field would provide the Americans with an important asset for the rest of the Pacific War.

Sixty years later, Abady was posthumously awarded the Silver Star for his role in the battle:

Citation:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to Second Lieutenant Herman Abady, United States Marine Corps, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action while serving as Platoon Leader, Company K, Third Battalion, First Marines, FIRST Marine Division on Guadalcanal, British Solomon Islands. On 13 and 14 September 1942, Second Lieutenant Abady’s platoon was deployed straddling an overland trail and bore the brunt of the attack on the company’s positions from a detachment from the Japanese Army’s Kuma Battalion whose objective was Henderson Field and the FIRST Division Command Post which were located approximately a half mile to the rear. Enemy Japanese soldiers with fixed bayonets penetrated the barbed wire less than 200 feet in front of the platoon’s position, and entered the unit’s foxholes where vicious hand-to-hand combat ensued. At one point, Second Lieutenant Abady took a position behind a banyan tree and succeeded in killing several Japanese soldiers with his .45 caliber pistol. As a result of his direction and encouragement, the Marines held their positions against the intense enemy onslaught and kept the enemy from reaching their objective. At daybreak, some 30 bodies of enemy soldiers lay around the platoon’s defensive positions and an additional 30 bodies were entangled in the barbed wire in front of the platoon’s position. By his extraordinary heroism, superb courage, and loyal devotion to duty, Second Lieutenant Abady reflected great credit upon himself and the Marine Corps and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

The battalion stayed on Guadalcanal until December. They endured not only more combat with the Japanese but exhaustion, debilitating jungle conditions, and lack of supplies. Abady was wounded with a gunshot to the leg. After leaving Guadalcanal, both Sager and Abady were sent to hospitals in the U.S. with bad cases of malaria. After recovering, Sager would serve in China with SACO, the Sino American Cooperation Organization. Abady stayed in the U.S. and trained Marines in amphibious warfare.

When writing about his 1942 Rosh Hashanah, Sager shared another anecdote of an encounter shortly before he left the island. The Army had arrived on Guadalcanal and, for the first time, a Jewish chaplain was on the island. Sager had heard the bugler call for church services on the previous Friday evening but the idea of a Shabbat service on Guadalcanal seemed inconceivable. When, a few days later, he saw an Army officer with Jewish chaplains insignia on his collar he said to him: “Then it was you having religious services on Friday night!” The rabbi assured him that there were indeed Shabbat services the previous Friday.

Sager described his intense reaction to the news that would be more formal Jewish services for those remaining on Guadalcanal. The arrival of the Jewish chaplain caused Sager to think of his comrades lost in battle there in recent months:

I sat on the edge of my cot and buried my head in my arms. For some reason which I shall never understand, I felt emotionally drained. My voice choked up. I didn’t want these two Army officers in fresh khaki to see that my eyes were moist. A hundred thoughts raced through my mind, but I could think of only one as I sat with my head buried in my arms. We who had existed through that terribly dangerous experience called Guadalcanal and now about to leave, would not be leaving our Jewish comrades alone and deserted in the military cemetery by the Lunga lagoon.

Abady and Sager remained friends for life. Abady died in 2001 and Sager in 2019.

For more on their experience, see Battle at the Overland Trail book and DVD by Herman’s son Jason Abady.