Frances Slanger moved to the United States from Poland in 1920 with her family. Settling in Roxbury, Massachusetts, she completed nursing school and enlisted in the Army Nurse Corps in 1943. She fought for her right to be sent overseas where the need for nurses was greatest, and was finally deployed in 1944 to the European theater.

Slanger was assigned to the 45th Field Hospital to aid casualties from the allied invasion of France. She was one of only four nurses who went ashore at Normandy after D-Day. On October 21, 1944, Slanger wrote the following to Stars and Stripes magazine:

It is 0200, and I have been lying awake for an hour listening to the steady breathing of the other three nurses in the tent, thinking about some of the things we had discussed during the day.

The fire was burning low, and just a few live coals are on the bottom. With the slow feeding of wood and finally coal, a roaring fire is started. I couldn’t help thinking how similar to a human being a fire is. If it is not allowed to run down too low, and if there is a spark of life left in it, it can be nursed back. So can a human being. It is slow. It is gradual. It is done all the time in these field hospitals and other hospitals at the ETO.

We had several articles in different magazines and papers sent in by grateful GIs praising the work of the nurses around the combat zones. Praising us – for what?

We wade ankle-deep in mud – you have to lie in it. We are restricted to our immediate area, a cow pasture or a hay field, but then who is not restricted?

We have a stove and coal. We even have a laundry line in the tent.

The wind is howling, the tent waving precariously, the rain beating down, the guns firing, and me with ta flashlight writing. It all adds up to a feeling of unrealness. Sure we rough it, but in comparison to the way you men are taking it, we can’t complain nor do we feel that bouquets are due us. But you – the men behind the guns, the men driving our tanks, flying our planes, sailing our ships, building bridges – it is to you we doff our helmets. To every GI wearing the American uniform, for you we have the greatest admiration and respect.

Yes, this time we are handing out the bouquets – but after taking care of some of your buddies, comforting them when they are brought in, bloody, dirty with the earth, mud and grime, and most of them so tired. Somebody’s brothers, somebody’s fathers, somebody’s sons, seeing them gradually brought back to life, to consciousness, and their lips separate into a grin when they first welcome you. Usually they say, “hiya babe, Holy Mackerel, an American woman” – or more indiscreetly “How about a kiss?”

These soldiers stay with us but a short time, from ten days to possibly two weeks. We have learned a great deal about our American boy and the stuff he is made of. The wounded do not cry. Their buddies come first. The patience and determination they show, the courage and fortitude they have is sometimes awesome to behold. It is we who are proud of you, a great distinction to see you open your eyes and with that swell American grin, say “Hiya, Babe.”

Only hours later, LT. Frances Slanger was shot in the field, and was the only nurse to be killed by enemy action in the European theater. Reports say that even as she lay dying, she was more concerned with the soldiers and other injured nurses receiving medical attention and treatment, as she had accepted her fate.

When Stars and Stripes received her letter, they were not yet aware of her death, and published it as an editorial. It was so inspirational to readers everywhere, that service members and civilians alike began writing her letters to thank her for her kind words, saying that she had helped restore some faith in humanity amidst the devastation of war.

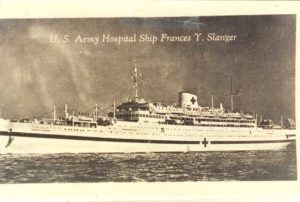

Frances Slanger was initially buried in a military cemetery in France under a Star of David, until 1947 when her remains were returned to the United States, and was reburied in her hometown Roxbury, Massachusetts. In 1945 the U.S. Army named a hospital ship Frances Y. Slanger in her honor.

- Profile: Aaron and Dan Schilleci

- Profile: Abe Johnson

- Profile: Alexander Goode

- Profile: Amram Cohen

- Profile: David Camden de Leon

- Profile: Edward Feldman

- Profile: Elkan Voorsanger

- Profile: Gerald Fink

- Profile: Hank Greenberg

- Profile: Harry Ettlinger

- Profile: Hyman Goldberg

- Profile: Isadore Kahn

- Profile: Jack Miller

- Profile: Jacob Heckman

- Profile: Julius Adler

- Profile: Kate Karpeles

- Profile: Kenneth Rubin

- Profile: Larry Liss

- Profile: Leo Rosskamm

- Profile: Louis W. Freedman

- Profile: Marita Silverman

- Profile: Melvin Garten

- Profile: Miranda Bloch

- Profile: Mordecai Sheftall

- Profile: Phoebe Levy Pember

- Profile: Solomon Isquith