Meyer Gilden's Art, Passover and the Liberation of Wöbbelin Concentration Camp

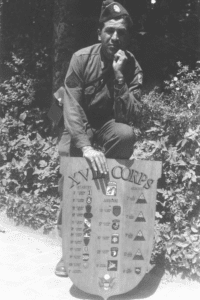

Meyer “Mickey” Gilden was born in Baltimore. He was living in Washington, D.C. working as a commercial artist when he was inducted into the Army in August 1943. He trained at Fort Dix and Fort Bragg. He was able to use his skills as an artist with the 643rd Engineer Camouflage Company and then as a draftsman with the XVIII Corps. He was sent overseas in July 1944.

Gilden primarily served with the XVIII Corps headquarters staff. He was at the Battle of the Bulge, Rhineland Campaign and the Battle of the Ruhr Pocket. Gilden painted signs with a secret code. This work placed him with advanced parties for certain operations. His letters describe the relentless fighting and watching wave after wave of aircraft fly above him.

Gilden’s artwork expresses what he saw during World War II. This painting shows dead and wounded amidst wreckage caused by the Battle of the Bulge. The hills of the Ardennes rise in the background. Medics are preparing to take a body on a stretcher to the ambulance. A dead body is in the foreground. There is some destruction, but the buildings are still standing (unlike much of the Ardennes which was destroyed). Your eyes are drawn to the face-down soldier who has given his life.

Gilden’s diary from his weeks in the Ardennes describes the beauty of some of the European scenery. He also writes about the near constant sound of German buzz bombs, his own fear of death and his reaction at seeing the dead bodies of American comrades. These contrasting impressions come together in the painting. An otherwise idyllic landscape is ruined by war.

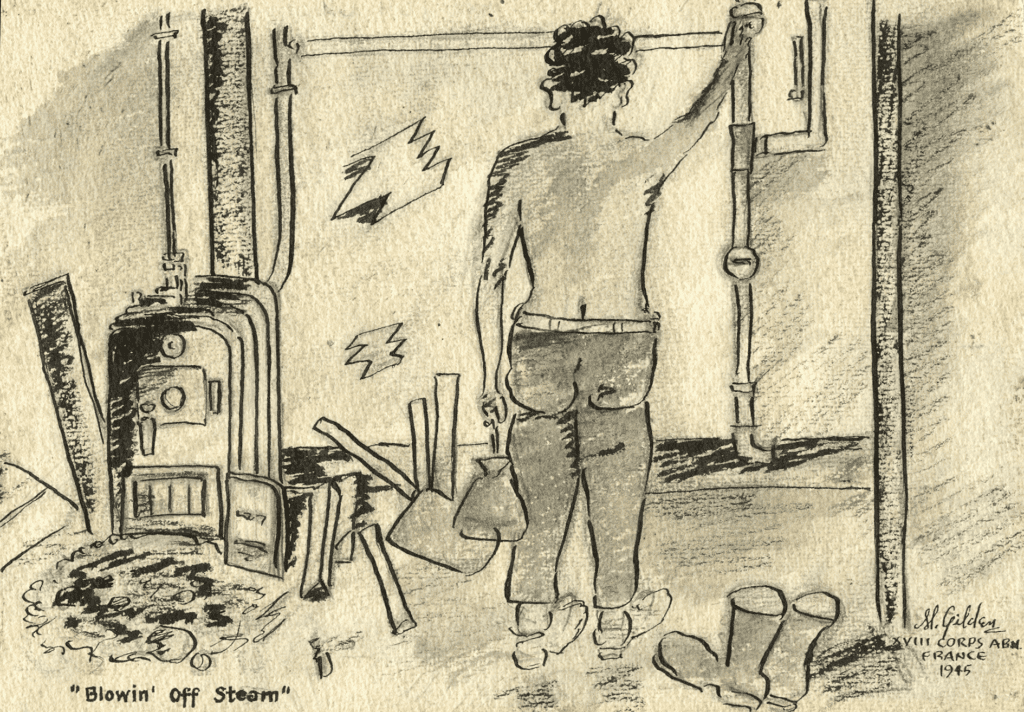

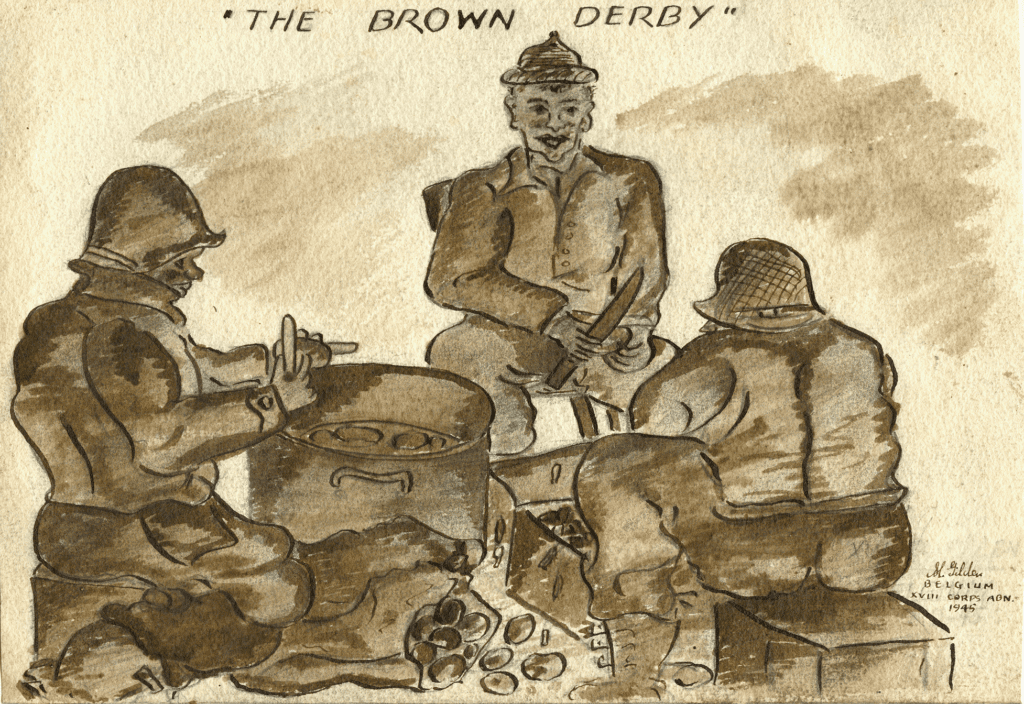

Other artwork depicted the more mundane daily life in the military during wartime.

Gilden’s artwork allowed him to establish a relationship with General Matthew B. Ridgway, commander of the Corps. Ridgway repeatedly commissioned pieces from Gilden including battle scenes like the one above, portraits of other generals and an official XVIII Corps Guest Book. Like his art, Gilden’s Judaism played a central role in his military service. He frequently conducted services in the absence of a Jewish chaplain. Near the war’s end, Gilden was assigned to be a chaplain’s assistant.

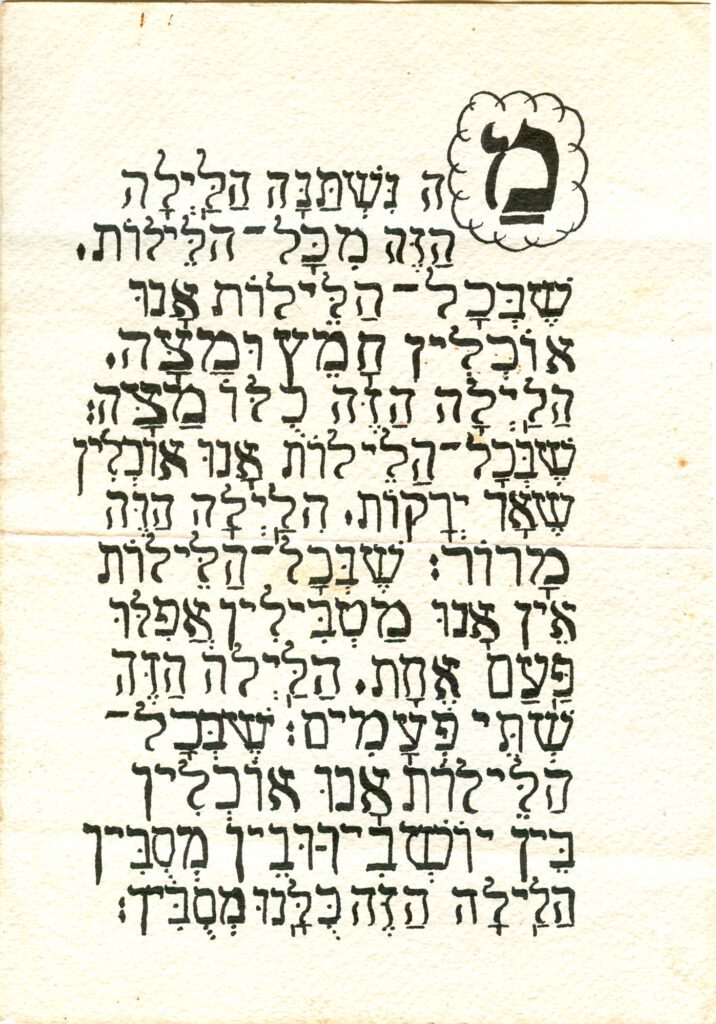

One of his most personal art projects was a beautiful script of the Four Questions he sent from Europe to his young son at home for their Passover Seder.

Passover 1945

Prior to Passover, Gilden thought of how he could not be with his son to celebrate. To incorporate the spirit of the tradition of the youngest reading the questions, he drafted this Four Questions, thinking of his son as though he were asking them himself.

The pen and ink document stands as a testament to the importance of Jewish identity during Gilden’s wartime service.

He included the draft for his son in a letter sent to his father-in-law from Germany. Gilden wrote:

“To be a Jew is not easy. It involves tremendous responsibilities. For if he is true to traditions, he must be a soldier for democracy. For what cause can be worthier of any man’s effort and life than that of defending freedom?

After sending his work home to his family, Gilden received the assignment to organize and lead a Passover Seder at headquarters as the Americans continued to advance through Germany.

The Seder was held in the officers’ mess hall. Many of the soldiers had been pulled forward in preparation for an assault on Wesel, Germany. Even the chaplains section had moved forward, leaving Gilden without supplies for the Seder. “Fortunately,” he wrote “I had come prepared with three books tucked under one arm, and my well oiled carbine slung over my shoulder, with hope for Victory in my heart and a speech for after the Seder.” He described the batteries of aircraft just outside the door while “an occasional Jerry soared over the field close to our barracks to drop an egg on the British Air Force Field.” Though not enough men joined to make a minyan, the Seder was underway when an MP ordered the lights shut off to prevent the Germans identifying them as a target. The group of Jewish soldiers tacked up black shades and resumed. “We carried on amid the din and clatter of anti-air guns and Hell… Blumey, Greeny and I couldn’t ‘daven’ in the dark…the business of killing had to go on uninterrupted by such small details as a mere little Pesach Seder. And so be it my dear, a night I shall never regret forget.”

A German bomb landed 500 yards away before the night finally quieted. At the end of the night, Gilden wrote to his wife to describe the Seder. He concluded the typed letter written with a handwritten line:

“Tomorrow is the First Day of Passover and may very well be the first real plague for the Germans.”

Wöbbelin Concentration Camp

About a month after Passover, the 82nd Airborne encountered Wöbbelin Concentration Camp where about 1,000 bodies lay, dead from starvation. Shortly after liberation. Meyer Gilden was called to the camp to stand guard. Like the other American liberators, Gilden was appalled by what he saw. Once he got past the corpses, he saw survivors. They had little food or water and had been living in deplorable conditions. Gilden described the barracks as “shocking and unbelievable… they were indescribably horrible, thick with slime and filth. The stench was unbearable.” Gilden interacted with three survivors who he found in an attic at the top of a staircase. They recognized that they’d been liberated, but had nowhere to go.

Seeing the importance of ensuring the German people recognized and acknowledged what had happened in the camps, the Americans ordered the people of the nearby town of Ludwigslust to bury the dead. Captured camp guards were made to dig the graves.

After the initial burial, public services were held in Hagenow, Germany, not far from the Wöbbelin camp. Again, American soldiers ensured German civilians would be in attendance. An address was delivered by Colonel Harry Cain. It was described by General Ridgway as one of the most effective speeches he ever heard. Cain placed blame for the atrocities squarely on the Germans who were watching:

“In these open graves lie the emaciated and brutalized bodies of some 144 citizens of many lands. Before they were dragged away from their homes, and their livelihoods to satisfy the insatiable greed and malice, ambition and savagery of the German nation, they wore happy and healthy and contented human beings. They were brought to this soil from Poland, Russia, Czechoslovakia, Holland, Belgium and France. They were driven and starved and beaten to slake that unholy thirst of the German War Machine. When possessed no longer of the will or the ability to work or fight back or live, they were tortured to death or permitted slowly to die. What you witness and are a part of in Hagenow today is but a small example of what can be seen throughout the length and depth of you Fatherland…”

Gilden described the German citizens as “impassive and stolid as they passed the open graves of these poor unfortunate human beings that they had murdered.” He created a 3 foot by 4 foot painting based on the experience with the words of Cain’s speech running through the center. He eventually donated the piece to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Gilden remained haunted by what he saw at the liberation of Wöbbelin Concentration Camp. The experience continued to inform Gilden’s art until he died in 2003.