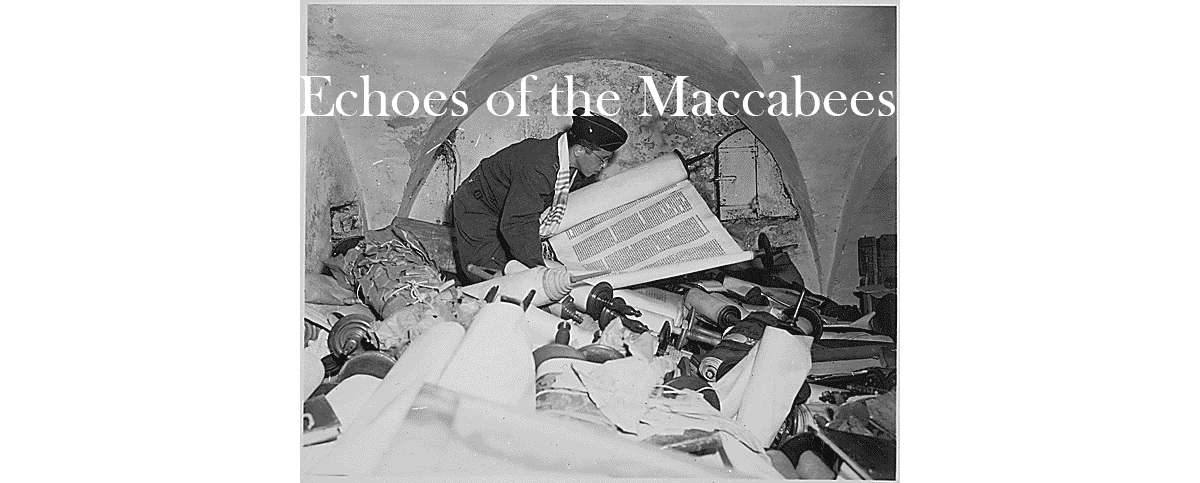

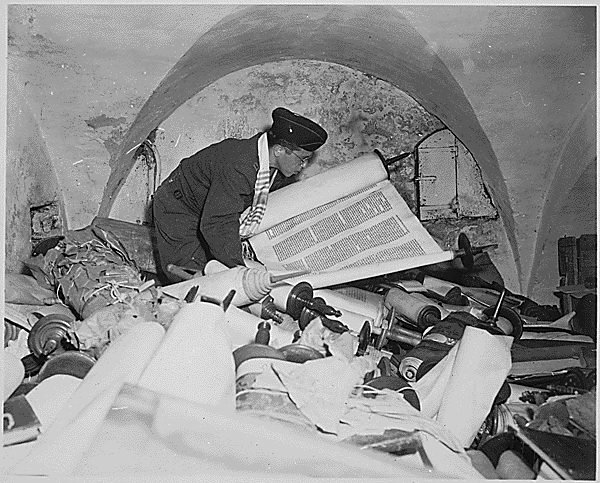

Echoes of the Maccabees: Restoring the Temple after WWII

By the summer of 1945, the war in Europe was over, but repairing the destruction was just beginning. In the Pacific, and particularly in Europe, synagogues had been damaged, destroyed, defamed. Some burned to the ground, others were used as houses for illicit activities like prostitution, some were turned into Nazi storage facilities. Those that still stood needed to be restored. Echoes of the Chanukah story from two millennia earlier rang out again in 1945. Like their spiritual forebears, the Maccabees, American Jewish service members followed their military victory over an enemy who sought to destroy Jews by restoring the temple.

After World War II, there would be no miracle of long-lasting oil. Instead the restoration of the synagogues was the start of a long-lasting, but perhaps equally miraculous task—helping to ensure a place for Jewry in Europe after the Nazi efforts to destroy it. American Jewish soldiers played a key role.

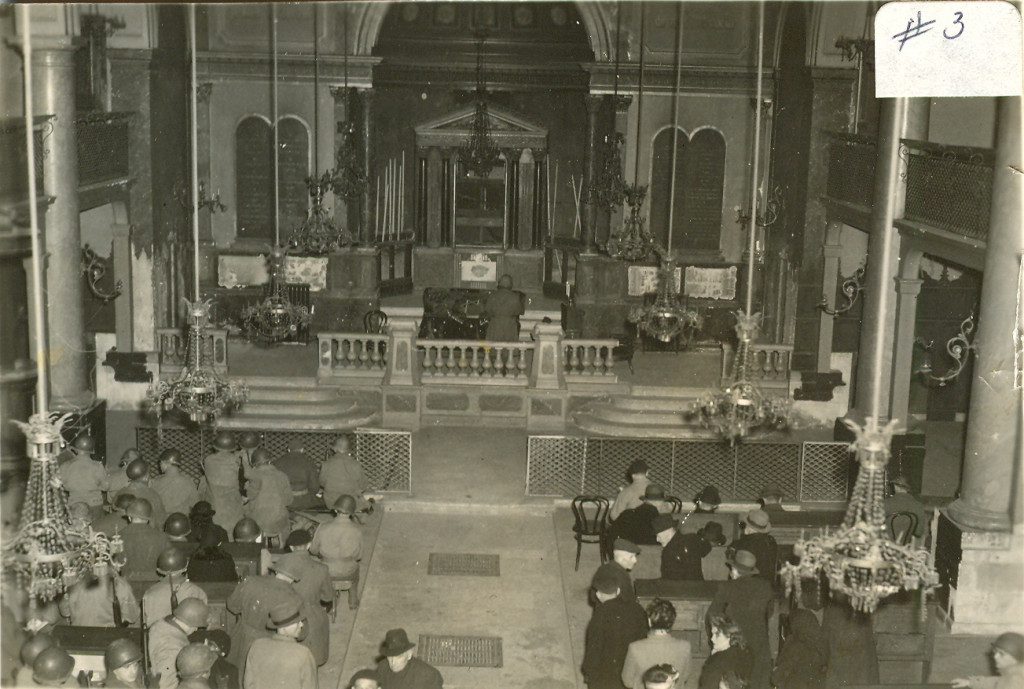

Jewish religious services in Europe in early 1945 were held in synagogues still badly damaged. But if the outer walls still stood, American soldiers would gladly attend services. The mere act of attending a Jewish service in Germany, or other places recently occupied by the Germans, was a statement of triumph over the Nazis. The American Jews who attended these early services recognized the need to undo the Nazis work. Restoring and rededicating synagogues was one way to do this.

These restoration efforts were often led by American Jewish military chaplains who enlisted Jewish service members to aid in the rebuilding tasks. Sometimes local German gentiles would also be included in the effort, often against their will. This was a part of the effort to force German civilians to recognize what the Nazis had done. American soldiers would also seek out surviving local Jews in places where they remained. The initial congregations of these restored synagogues consisted primarily of Allied service members who remained in Europe. They worshiped at the temples they had restored as they hoped there would soon be a local Jewish community to return to these areas and reclaim the synagogues as their own.

In a letter written home on May 12, 1945, Joseph Levin described a typical scene where American Jewish soldiers were needed to restore a synagogue “somewhere in France:”

“Last night I went to services at a synagogue in the nearby town. It was the first Friday night service that was held there in 5 years — since before the war. It is almost the only building in town that was damaged by the Nazis. Practically the entire town was kept in good shape by the Nazis because of the champagne production. The synagogue was about the only building to be ruined.

Although most of the walls are in tact, everything inside was ripped to shreds. All windows were smashed, all fixtures ripped apart. We were told that all Torahs were shipped to Bordeaux (a city on the west coast of France) where they all were burned. We are going to try to help put the building back in halfway decent shape in our time off. We were able to hold conversations with the people here by speaking a little French, a little German, a little Yiddish, and very little English.”

In other parts of Europe, restoring the synagogues often coincided with efforts to care for displaced persons from all over Europe at the war’s end.

The Philippines: Temple Emil

This echoing of the Chanukah story was repeated over and over again across the world with American Jewish service members playing the role of the Maccabees. It wasn’t only the Germans who sought to destroy synagogues. In one example in the Philippines, the Japanese burned out the interior of Temple Emil, a Manila synagogue. The Japanese occupation of the Philippines had been brutal. Destruction was rampant and the only synagogue on the island had not been spared damage.

The Japanese, with their usual ruthlessness turned the arsenal of faith into an ammunition dump.

In the 1930s, there had been approximately 500 Jews in the Philippines. Many of them were Russian refugees who had left to escape pogroms and persecution. Temple Emil was their refuge. This refuge was destroyed by the Japanese.

After the war, the Jewish community had shrunk. There were no longer enough Jews on the islands to work to bring the synagogue back to usable conditions. It fell to the Americans to restore Temple Emil.

A group of service men and women felt the need to leave an enduring memorial for their Jewish comrades who valiantly gave their lives. They undertook the rebuilding of the synagogue which had been first built in 1922. According to Jewish Welfare Board records, a committee was formed of Chaplains Colman Zwitman and Dudley Weinberg with Captain Adolph R. Nachman, Corporal Irving Weinberger, Lieutenant Leonard Schatz and others. Their goal was to work with the few remaining Filipino Jews to restore the synagogue. They staged a campaign that involved 1,500 GIs.

A group of service men and women felt the need to leave an enduring memorial for their Jewish comrades who valiantly gave their lives. They undertook the rebuilding of the synagogue.

“A Memorial service in the ruins of the only synagogue in the Philippines will inaugurate the Reconstruction Project. The service will be held on Nov. 9th to commemorate the 7th anniversary of Nazi Germany’s wholesale burning of synagogues. To the Japanese went the infamous distinction of burning the Manila synagogue – the only synagogue under the American Flag destroyed by the enemy in this war. In 1944, the Japanese with their usual ruthlessness turned the arsenal of faith into an ammunition dump. When the American forces returned in Feb. 1945, the Japanese blew up the building. The outer walls still stand.”

This document describes the American effort which would include a plaque to the Jewish War Dead to stand inside the rebuilt synagogue:

Interestingly, the document notes the efforts of Jewish service men and women the European Theater of Operations in reconstructing the community of European Jewry. The author notes that for those in the Pacific reconstructing Temple Emil is “our opportunity.”

Indeed by November, when this was printed, many synagogues of Europe had been reconstructed and rededicated with American service members playing key roles. In the Philippines, the effort was completed in December of 1945, when Lieutenant General Wilhelm D. Styer, Commander in Chief of US Army Forces—Western Pacific, presented money raised for rebuilding the synagogue to the local Jewish community.

Chaplains in Europe

In wartime, chaplains would hold a service anywhere they could. There were outdoor temples, makeshift bunker chapels, airfields turned into houses of worship, even “Methodist Shuls.” Of course, the ideal place for Jewish services was a synagogue. Thus, the Jewish Chaplains played a crucial role in the restoration of synagogues in 1944 and 1945.

Chaplain David Max Eichhorn described a quick restoration to the synagogue in Luneville, France to get ready for Yom Kippur services. This occurred when it was still unclear if the Germans held positions in the area around Luneville:

“The synagogue was indescribably filthy. It and the Rabbi’s house next door were inhabited by about a dozen youne enciente French females, whom the retreating Germans had impregnated and abandoned… Local workers removed four ox-cart loads of dirt and debris from the synagogue. The place was scrubbed clean, temporary electric lights were installed and the tattered remains of prayer books were gathered up reverently and placed upon the altar as a mute remembrance of 300 Luneville Jews who had been transported by the invaders to the death-chambers of Auschwitz. Finally the synagogue was decorated with American and French Flags.”

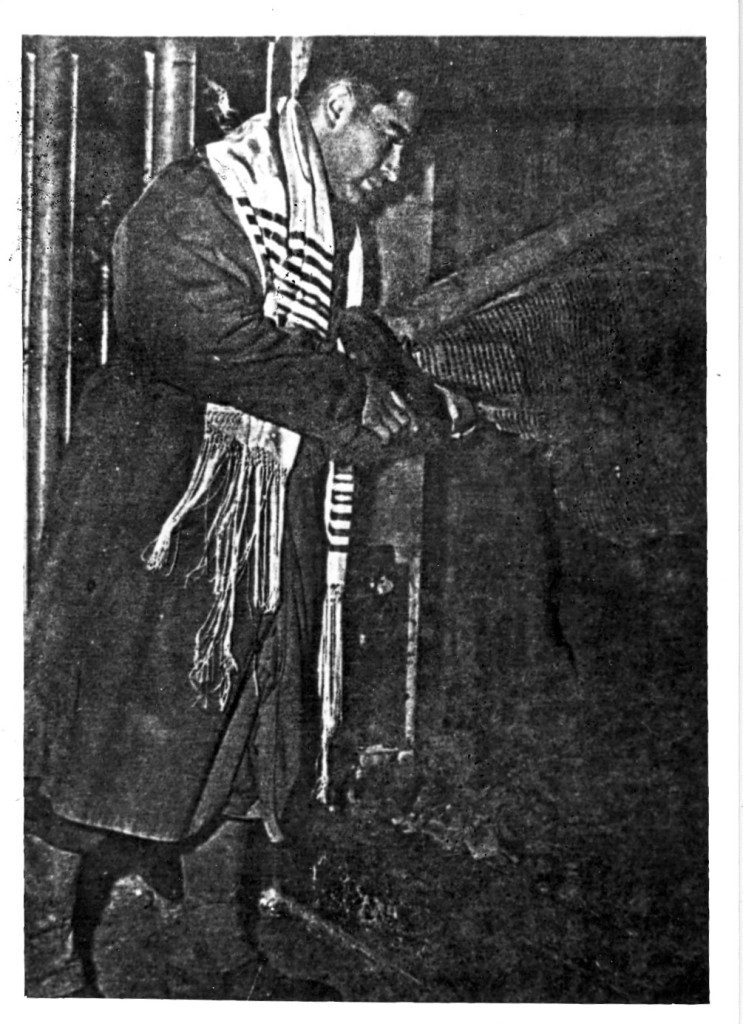

Chaplain David Max Eichhorn

Eichhorn was still unsure if they would be able to hold services as “the walls shook from endless artillery fire.” Though Luneville was still not officially taken by the Americans, 350 Jewish service members risked their safety and arrived for Yom Kippur. “The noises of battle raged around us as we intoned our traditional prayers… It was for many of them, the last religious services they would ever attend.

Chaplain Herman Dicker rededicated the Grand Synagogue in Metz which previously had been converted to a house of prostitution. The caption of the photo states: “It has been cleansed of this abomination by the chaplain, Abe Plotkin, and a few others of the 5th Division of the 3rd Army.”

These scenes occurred throughout Europe. It was important to many American Jewish soldiers to set things right and do what they could to restore Jewish life.

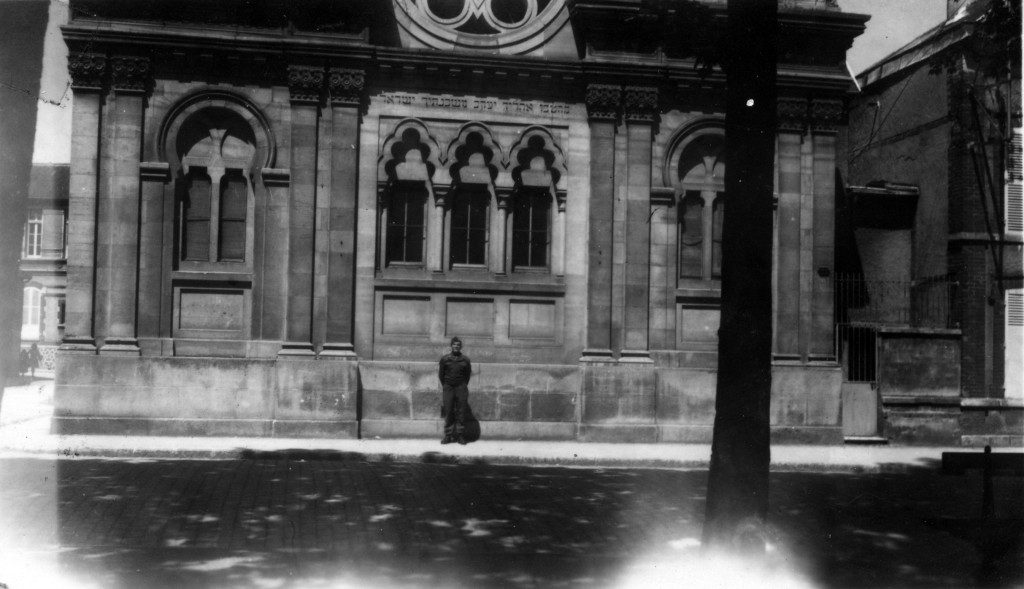

Epernay, France

PFC Meyer Gilden was serving with the headquarters staff of the XVIII Airborne Corps in Europe in 1945. He described the rehabilitation of the synagogue at Epernay and the surrounding events where he met local French Jews:

“June 1st, about three weeks after V-E Day, the synagogue in Epernay was going to open that evening for the first formal religious services to be held in this ancient town in 5 years. Just a week before, this holy place of worship was a scene of utter ruin and disrepair. But a Jewish Chaplain came to the corps and took immediate steps to rehabilitate the synagogue with the energetic efforts of Jewish military personnel from the 605th Engineer Battalion.

The Magen David; the huge star which had been in a niche in front of the shul and had been blown into the shul by bombing was restored. The Ark itself received a dramatic restoration. The most important item, the Sefer Torahs were contributed from other sources and brought in. Quite a lot had been accomplished in such an incredibly short time, a remarkable feat indeed. Much work still remained to be done, such as more replastering and painting and the continuing replacement of much of the woodwork. The outside of the synagogue was rather impressive with it’s granite blocks and fancy carvings. At the beginning of the service that evening the president, a Monsieur Cafleur spoke in French and English expressing his appreciation for everything that was done and contributed by the U.S. Army followed by a speech by Corps Chaplain Rubin.

The synagogue that evening overflowed with many French Jews, Jewish servicemen and officers. Two days before this event, one of the congregants invited me and Sergeant Mantell, the band conductor, Warrant Officer Margolin, Corporal Gisbard and two Jewish members of the Engineers to his home for dinner and drinks. It was a warm evening and so we strolled over to our host’s (Monseur Fossberg) home. MMD Fossberg greeted us warmly.

Their son had also been at the shul that evening. The following is what we had: First off, shots of whiskey in tiny odd looking glasses. The large table was tastefully arranged with an excellent French service. The Fossbergs bad been engaged in the clothing business and were at one time very wealthy, until the Boche compelled them to seek refuge in the south of France. At the table was plenty of delicious French bread (no Chollah). They served us kippered herring which had been sent to them in cans by an uncle in Brooklyn. This was followed by lots of roast chicken. Then Madam Fossberg brought in a big steamingly hot kugel, which we all devoured·eagerly. Bottle after bottle of good rich French wine was served during the entire meal. Our dessert was big delicious red strawberries which we washed down with good champagne.

After dinner we sang and related our various experiences. Officer Margolin, somewhat of a scholar, gave us a lengthy translation from the Talmud by memory. A very gifted man and capable of playing any musical instrument. It was close to midnight when we left after thanking our wonderful host and hostess. “

PFC Meyer Gilden

Jews who had avoided the Holocaust were much more prominent around Epernay then many parts of Europe. The opportunity to connect with them in the act of restoring their synagogue proved to be one of the most memorable parts of Gilden’s war experience in Europe.

Rome

Pvt. Charles Golub of Worcester, Massachusetts had a similar type of connection with Jews in Italy. When the synagogue of Rome reopened its doors for the first service since it was closed by the Nazis. Golub was honored by being called upon to recite a blessing. He described the occasion in an account printed in his hometown newspaper:

“You should have seen the happy expression on the people’s faces. It was really a soul-stirring spectacle when the Jewish synagogue opened and prayers in thanks for liberation were offered. And I was called upon to ask a blessing. Many people shed tears of joy when the allies great victory was realized. Plenty of them stopped to talk to me and you’d have thought I was a general they way they all gaped! There is so much I’d like to tell you… If God will only protect me as he has in the past I’ll have much to be grateful for.”

Pvt. Charles Golub

Golub did survive the war and the rededication of this synagogue remained a key aspect of his memories of the liberation of Rome.

Nancy, France

Occupied by the Germans since 1942, the Jewish population from Nancy, France was largely deported out of the area during the war. The city was liberated by the 3rd Army in September of 1944. The high holidays were around the corner. Though the exterior walls stood, the Nancy synagogue been gutted by the Germans and turned into a storage facility. It had to be cleaned and restored in time to hold a Yom Kippur service. American soldiers did enough work to make the building usable and services were held on September 27, 1944.

Synagogue at Nancy France before and after clean-up for high holiday services

In a letter written home to his parents that was reprinted in the newspaper, future Las Vegas Sun publisher Hank Greenspun described the Nancy synagogue and the service that Yom Kippur:

“It must have been a beautiful structure, judging from the tremendous walls that had been formerly lined with brass fittings. The brass is missing. The copper frames of two giant tablets containing the ‘Ten Commandments’ in Hebrew and French are also missing. The place where the Torahs were kept was destroyed by an ax. The chandeliers were all ripped from the ceiling and sent to Germany. The organ must have been a massive affair, built into the rear wall, which has since been broken open, and each pipe of the organ was individually broken. There must have been 50 pipes ranging from real small ones to very large ones, and each and every one was painstakingly and systematically destroyed. The keyboard was wrecked with an ax.

“The pulpit was built at the side of the temple with stairs leading up to it. The ‘Boche’ first removed all the fittings from the pulpit and then smashed the stairs leading to it.

“Stained glass windows were left intact in the bottom floor, which was being used as a warehouse. However, the upper stories were not necessary for the German war effort, which meant that the windows had to be smashed and they were. The outer doors had a lot of German written on them, but it seems that every work was ‘Verboten.’ Inside the walls were chalked with ‘Ferichte Juden.’ (Crazy Jews)….

“The Torah was given by the Catholic caretaker who hid the Torah and the Menorah for four years, while the Germans searched high and low for it. She had also hidden a few prayer books that the Germans overlooked when they burned all the books.

“One of the civilians prayed for the congregation while a soldier with a very good voice acted as cantor. All through the services the 86-year-old woman, who was present only because some nuns had hidden her away, kept crying. She was joined by a man whose son was killed and when they said the Memorial for the Dead, all the civilians really went to pieces.

“Some of the soldiers, who were present because of having one of their parents dead, cried also. Not so much for their parents, I believe, but out of sympathy for these people, who lost everything and went through five years of a living hell.”

Hank Greenspun

The extraordinary emotional response to the return to the synagogue connected the European Jew with the American Jewish soldier. They both were just beginning to process the impact of the war and the horrors of the Holocaust.

Bad Nauheim, Germany

The Jewish community of Bad Nauheim, Germany dated back to the middle ages. In the 1930s, there had been several hundred Jews in Bad Nauheim who had dedicated a new synagogue in 1928. The condition of the synagogue was described in the newsletter IX Corps Scroll, published on June 24, 1945.

“On visiting the synagogue for the first time, [surviving German Jew Peter Busse] found it a storage pit of iron, hemp rope, steel rope, and other heavy material. The walls were covered with fecal matter, the windows were broken, the floors damaged and torn up. There were no pews left at all, the Almemor and pulpit were destroyed.

Within 8 days, the iron store had been removed and on April 27th, the first divine service was held by the American Chaplain Feldheym.”

Led by another American Jewish Chaplain, Samuel Blinder, the synagogue at Bad Nauheim was officially rededicated with a a service on June 24, 1945. For the occasion, Blinder wrote:

“Not only have the Jewish people been devastated, but their institutions as well. Schools, hospitals, libraries, synagogues. Of the latter, very few remain in Germany. Most of them have been burned, razed to the ground, and the few that remained were used by the Nazis for warehouses, shop, or as a dumping place for all kinds of junk.

Because of this fact we are particularly happy, to celebrate today the Dedication of the restored Synagogue in Bad Nauheim. Though none of the Jewish community remain, it will serve as a House of Worship for American Soldiers of Jewish Faith. And if ever a Jewish community returns to life here, then they will have this synagogue for their use.”

Chaplain Samuel Blinder

The rededicated synagogue served American soldiers stationed at Bad Nauheim, where the 12th Army was headquartered after the end of the war. Private Martin Glembourtt described attending Shabbat services there around that same time.

“One Friday evening, I attended a sabbath service there. When I entered the synagogues I found it filled with GIs from many of our units in town… There were many plaques on the wall dedicated to hidden Jewish townspeople. There were many plaques on the wall dedicated to those who had been slaughtered by the Germans. The dais was covered with flowers.”

Private Martin Glembourtt

Chaplain Blinder’s hope that one day the synagogue would be returned to German Jews was fulfilled. The synagogue continues to serve the several hundred Jews of Bad Nauheim today.

Modern Maccabees

It wasn’t unusual to see Jewish World War II soldiers referred to as modern Maccabees during and after the war. Though this almost always referred to their status as warriors. Equally notable is their Maccabean-like work restoring the temple and returning synagogues across the world into usable condition. The Nazis had tried to destroy Jewish life in Europe. It was an important step for restoring Jewish community in places the enemy had tried to destroy it. American Jewish service members became a part of many of those local Jewish communities in places far from their homes. For many, it was these experiences that went on to shape their post-war lives including becoming important members of their Jewish communities back home.