A series profiling American Jewish service in the First World War

Dr. Joseph Linett

Bad News From the Home Front

A raggedly dressed drunken horde raged through the market place in the town of Vinnitsa, Ukraine, on April 3, 1905, stoning windows, throwing over carts and tearing apart and destroying goods in any establishment that looked like or had a Jewish name. To wear a skullcap meant being spat at, beaten with clubs and sticks. Women were raped. Youssef Morris Linetsky had enough of this hate and prejudice and soon after migrated to the United States at the age of seventeen with only seven dollars in his pocket.

He and a cousin who joined him on the trip took up residence in New York City. Joseph Linett soon realized that if America was the door to opportunity, education was the key. While working as a machinist, he attended Trinity College where he earned a Bachelor of Arts in 1911. Two years later he matriculated at Columbia University where he eventually graduated with a Doctor of Medicine degree in 1917.

Shortly thereafter, the U.S. Army inducted him into the Medical Corps with the rank of lieutenant. Initial training took place at Fort Oglethorpe in northwest Georgia.

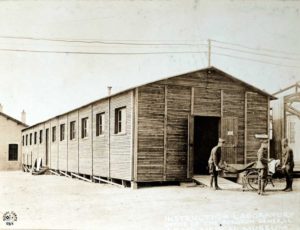

His next assignment took him to the medical department at Camp Bowie, a large training installation in Fort Worth, Texas. In the months just before he arrived the base suffered from a major measles and pneumonia outbreak afflicting more than 8,000 soldiers with 205 dying from complications.

Working in the receiving area, Dr. Linett evaluated prospective patients for admission. He sent some back to their duty stations and others to the hospital’s various wards such as surgical, isolation, neurologic, psychiatric and medical for further treatment and care. The patients’ personal items were taken from them, cataloged and stored in this section.

The Fort Worth Jewish community welcomed the soldiers and offered support to these patriotic Americans from Camp Bowie and other bases in the area by inviting them into their homes, and congregations for holidays and other occasions. The Hebrew Institute, a community center in downtown Fort Worth, entertained the troops with dances and parties. At one of the social programs, Joseph met and fell in love with an intelligent, beautiful young lady, Pearl Brown. Her father, David, had served as president of both Fort Worth’s Jewish houses of worship at different times. After a brief courtship, Joseph married her on April 20, 1918.

Unfortunately, the Army shortened their life together in July when they deployed Dr. Linett to France. Soon after he left for the battlefront, Pearl, his sweetheart and wife of only three months contracted Spanish influenza and passed away. More than five hundred people died from the malady in Dallas and nearly 300 in Fort Worth. Military bases were rife with the disease. The epidemic first hit Camp Bowie in September 1918 where medical officers issued an immediate and complete ban preventing soldiers from meeting at movie theaters, pool halls or dances on base or in the city. Instituting these rules resulted in lowering the incidence of the malady. When similar interventions were not employed in facilities and cities elsewhere in Texas and the country, massive outbreaks occurred with higher rates of morbidity and mortality.

With the limited communication and transportation in that era, he did not learn of Pearl’s demise for several weeks. He was not able to get transportation back to Texas until the war ended.

Assigned to Evacuation Hospital No. 1, the physician treated the wounded from the 82nd Airborne and several other divisions that fought in the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Forest battles. If a soldier sustained a wound, he first received medical help such as bandaging and splinting at a Battalion Aid Station immediately next to the front lines. If not badly wounded, medical workers sent combatants back to battle. If further care was necessary, transportation by motorized or horse drawn ambulance moved the soldier to a field hospital. These were close enough to the fighting that enemy artillery fire intermittently hit them. Fighters with more severe wounds requiring complicated treatment or surgery were sent by rail or ambulance to Evacuation Hospitals like the one that Dr. Linett helped staff. The Army constructed these next to railroad tracks ten to fifteen miles behind German lines, well beyond the reach of hostile fire. Patients could remain at these hospitals for up to two weeks with an average stay of eight to ten days. From there they were either transported for additional convalescent care or sent back to the front by rail.

An armistice ending hostilities in World War I was declared on November 11, 1918. A large residual force of United States servicemen remained in Europe as part of a peacekeeping/occupation army through most of the summer of 1919. French officials began seeking American students for their higher education institutions. This plan evolved with offers to almost six thousand demobilized soldiers. One of those, Dr. Joseph Linett, joined with an American detachment and studied medicine at the Aix Marseille.

He received an honorable discharge in August 1919 after debriefing at Camp Travis in San Antonio. When he returned to Fort Worth, he visited his wife’s grave and was a guest at the home of her parents, Mr. and Mrs. David Brown. He remained in Fort Worth for a time. However, he eventually returned to Brooklyn where he began the private practice of medicine. There he met Sadie Locke whom he married and began to raise a family.

Dr. Linett is a great example of a person who leaves his country of origin under dire circumstances and travels to the United States for freedom and a better life. He, as well as others, understood that with hard work and education they could contribute to society and build successful lives. In turn, they served their adopted country in her time of need even during dangerous and at times tragic circumstances.

Note: A version of this article will appear in Dr. Julian Haber’s upcoming book The Yanks Are Coming Over There, Over There. The book is a joint project of JWV Post 755 and Fort Worth Jewish Archives. Funding provided by grants from the Dan Danciger JCC Hebrew Day School Supporting foundation and Tarrant County Jewish Federation.

The author wishes to thank Mr. Robert Linett for providing a great deal of family, personal and other research for this article.

Revised versions of They Were Soldiers in Peace and War Vol. I and Vol. II tell the stories of more than one hundred Jewish American Service men and women, WWI through our current conflicts and was published in 2015. They are available in our museum store.